The steam hammer

A speech given at the Arthur C Clarke Centennial on the 16th of December, 2017, Colombo, sharing some brief thoughts on how AI will shape our future.

In which I introspect about the state of Indie publishing as of 2019.

Written January 18, 2019.

The Wild West of indie publishing is settling down. Here’s a glimpse of [what I think] is the future. Thoughts distilled over multiple conversations with R.R. Virdi, a great friend and occasional writing partner.

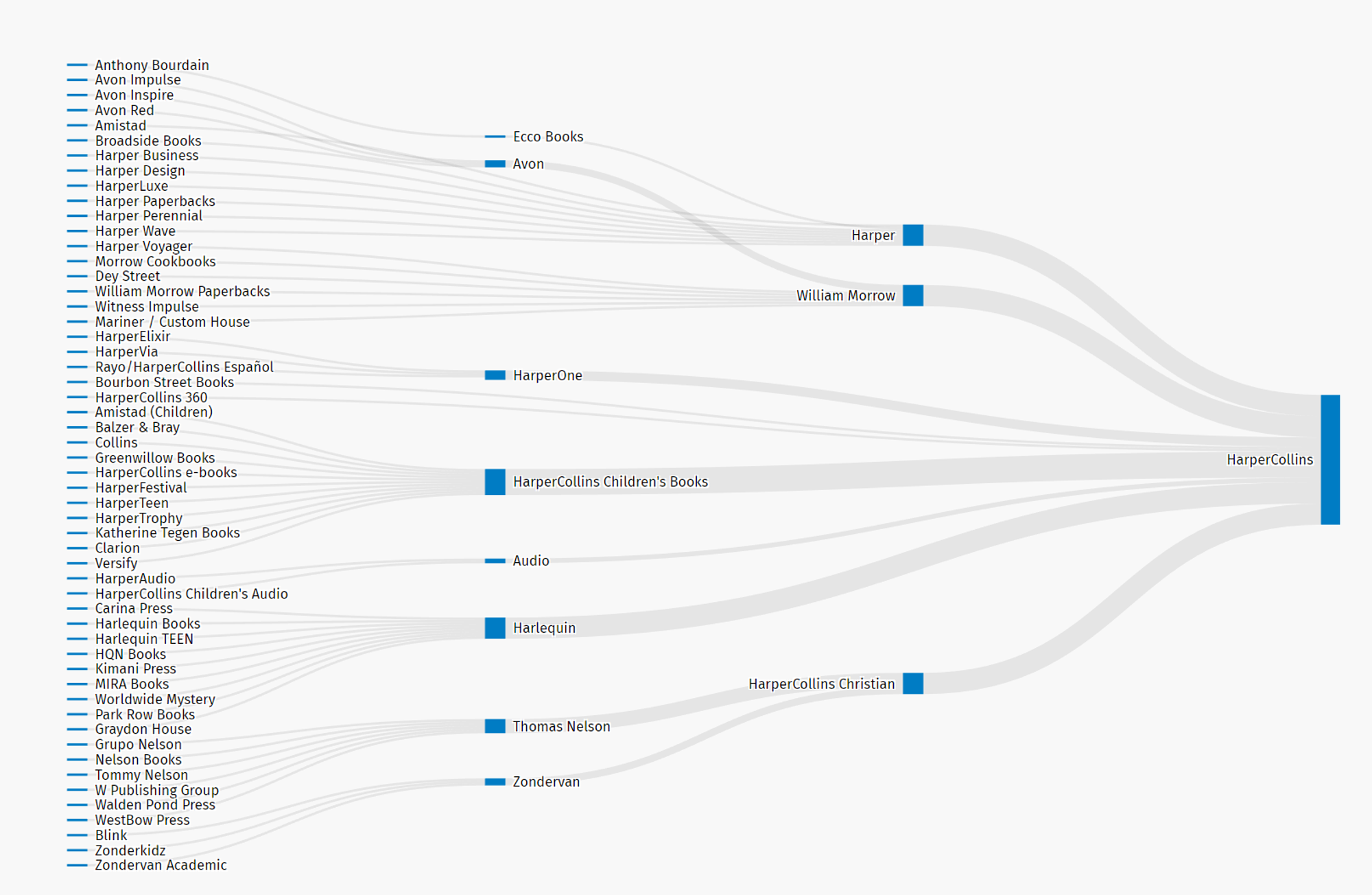

There are five big companies that own much of traditional publishing (TradPub) today[4]. Regardless of what imprint you see on a cover, the book in your hands is most likely from Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, HarperCollins, McMillan or Hachette. They are megacorps. Here, for example, is HarperCollins, which publishes my work.

And then there is indie publishing. While articulate naysayers still exist[1] (most recently with regard to Maroc Koskas’ Renaudot-longlisted novel[2]), indie publishing not a tradition new to literature – Walt Whitman, Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf all self-published their work[3]. Let us therefore burn snobbery at the stake and read. I’ll lump two types of indies into one umbrella: small indie presses that go after particular styles and genres[5], and indie authors themselves.

It’s very difficult to achieve fame and fortune with physical books in the indie space – one needs to invest in printing, shipping, warehousing and all manner of capital-intensive projects, not to mention breaking into the distribution channels traditionally owned by TradPub. These are meatspace[6] problems.

With the rise of Amazon and other storefronts, these problems have been largely solved for a sizeable number of readers. This is what I think of as the Amazon model:

Various services can hook into different parts of this ecosystem (Draft2Digital, Reedsy, Vellum, Mailchimp et al) to provide superior functionality; however, the basics exist and an author can finish a manuscript, neatly evade the meatspace basics, and be read from Colombo to Columbia in under a minute. Thanks to the higher royalties, said author can earn far more per reader than a traditionally published author.

Thanks to this Amazon model, self-published authors like Hugh Howey, Mark Dawson[7], LJ Ross and others became extremely financially successful[8].

As of late, traditional authors have begun to make inroads into this world. One of them is Brandon Sanderson, the living juggernaut of epic fantasy. Myke Cole was thinking about it as far back as 2013. Mark Dawson, a former trad-pubbed author who is now a key figure in the thriller genre, argues that trad publishing could be the new form of vanity publishing. There are many others, and not enough space to list them all.

Why this switch?

This 2018 piece from the New Statesman[9] provides a great summary of the situation:

“…a dramatic report published by Arts Council England (ACE) in December has raised the spectre of the highbrow novelist as an endangered species – and started a combative debate about how, if at all, writers should be funded.

The study claims falling book prices, sales and advances mean that literary authors are struggling more than ever to make a living from their fiction. In today’s market, selling 3,000 copies of your novel is not unrespectable – but factor in the average hardback price of £10.12 and the retailer’s 50 per cent cut, and just £15,000 remains to share between publisher, agent and author. No wonder that the percentage of authors earning a full-time living solely from writing dropped from 40 per cent in 2005 to 11.5 per cent in 2013. To avoid novel-writing becoming a pursuit reserved for those with independent means, ACE suggests emergency intervention: direct grants for authors and better funding for independent publishers and other organisations.”

Simply put, it takes a certain amount of financial security to be able to put one’s feet up and keep the pen on paper. Traditional publishing no longer provides this surety.

It’s easy to picture such indie publishing as a sort of digital Wild West, then, where lone authors venture forth into the desert heat, keyboards blazing, and claimed their fortunes, eager to defy the trope of the famous but starving bohemian artiste.[10]

However, indie publishing has evolved beyond being just an avenue where one can publish anything and earn a living. The Kindle Gold Rush, if it ever happened, is an event of the past.

Game industry consultant Christian Fennesbach, in a fine opinion piece, observed that in video games, franchises – and the franchise potential of intellectual property – are key to longevity[11]. He posits four key elements required for an intellectual property to become a franchise:

This is wisdom that has long been circulating in the publishing community in some form or the other (including the phrase you have to write a series). In the indie space, from my observation, this franchising happens along a more organic route:

Often an author creates a popular, genre-focused Intellectual Property (often in the form of a fictional universe with strong characters). The reader demand for it outstrips the supply. This is, in effect, a franchise with potential.

The author then goes on to collaborate with multiple co-authors to produce a series of novels, with the founding author playing the role of publisher and chief creative. They provide the vision and/or story outline, does a smaller percentage of the writing and the co-author takes on the larger share of the work.

Today, the indie publishing space seems to be trending towards such collaborative publishers (CoPubs). CoPubs function a bit like medieval foundries – a master smith at the center, aided by a number of lesser-known apprentices. The business model is often structured so that partners generally have long-term skin in the game: advances are rare and small when existent; profits are derived from royalties, split along much more equitable models than traditional publishers. I’ve seen contracts that go anywhere from 30% to 50% – large figures compared to the 7% of trad pub.

Less often there are equal partners in the enterprise – two smiths hammering away in a collaborative fashion, sharing half the workload and half the profits.

A key advantage of this model is speed and continuity. Fans benefit from the extremely rapid rapid release cycles possible with this method, and the CoPub itself can pivot quickly to add, expand or modify stories with sales potential. As the CoPub earns, it invests in advertising – primarily digital – to push its books.

In a sense this is similar to James Patterson’s business model[12], the fan-service of Charles Dickens[13] and, more recently, the business models behind Robert Ludlum or K.A. Applegate’s Animorphs[14].

The most successful CoPubs perfectly marry Fennesbach’s’s four elements to speed. Just as Patterson outsells Stephen King and John Grisham combined, CoPubs can outsell solo operations with less effort. Few single authors can compete with the prodigious output of work in a franchise that fans ardently love.

The most known within indie circles is perhaps LMBPN Publishing,[15] which operates Michael Anderle’s Kurtherian Gambit universe. Sterling and Stone[16], WaterHouse Press[17], the Nick Cole-and-Jason Anspach Galaxy’s Edge and Chris Kennedy’s Four Horsemen – co-created with Mark Wandrey – are others.

A light analysis would suggest that CoPubs become the new traditional publishers. More authors gravitate to CoPubs, profit accumulates, imprints acquire capital. The CoPubs cast down the Big Five of TradPub, diversify outside the digital book space and start shaking hands with airport bookshops and film executives, and in a generation or two there are the new megacorps- the Fat Six, or the Magnificent Seven, et cetera, et cetera.

This state of affairs continues until some upstart indie wordslingers figure out a new model, and the Wild West begins and ends all over again.

Possible. It’s a perpetual David-vs-Goliath story, and we love those stories.

But I happen to think there’s another future.

Firstly, CoPubs are smart. At present CoPubs are small fiefdoms that compete whose chief creative direction seems to stem from one person in the middle – aka one master smith. Dunbar’s number suggests a limit to the number of relationships that can be maintained by one person[18], and there is presumably a size at which a fast corporation becomes a slow, lumbering giant, so this suggests that there is a peak size at which a CoPub operation will halt, if only to preserve its agility.

Secondly, trad pub authors should be factored in terms of the attention economy[19]. The difficulty of forging a full-time career through trad pub alone[20] appears to be forcing midlist authors to contemplate indie.

Traditionally published wordslingers who sell well sometimes set up their own publishing imprint to manage affairs – the Tolkien Estate, J.K. Rowling’s Pottermore or Brandon Sanderson’s DragonSteel Entertainment are two examples. Our sample space is terribly limited, but imagine top authors handling the publication aspect for favored authors and giving them a push by slapping “JK Rowling presents” or “Brandon Sanderson presents” on top. That would mobilize a legion of fans, and said legion many be large enough to sell as many copies as a CoPub. There’s plenty of precedent for this in anthologies.

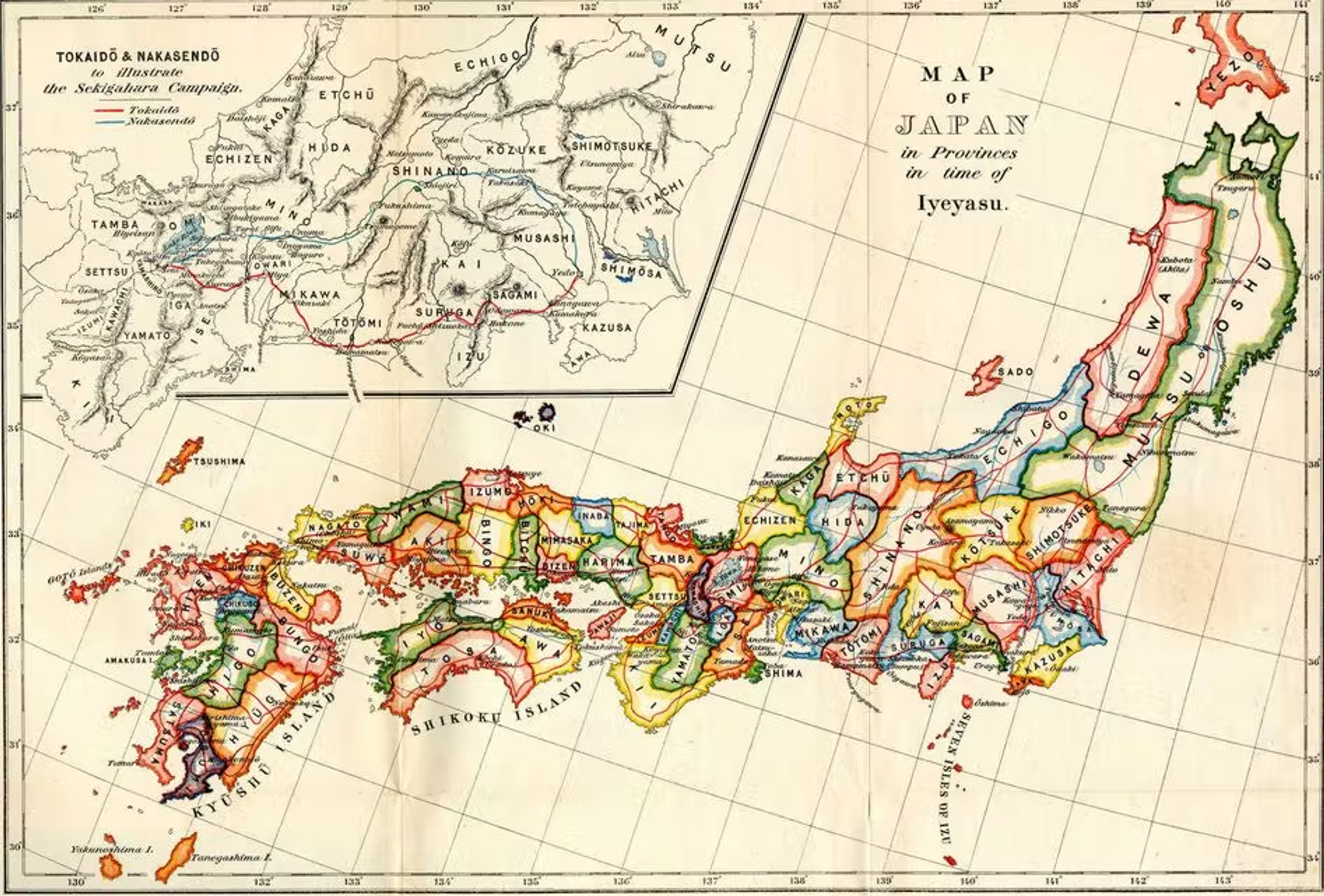

Thus, I think we’ll end up with a state of affairs where the fastest authors lump themselves into one set of operations, the bestsellers and their proteges/peers lump themselves into a slower set of operations, and everyone competes for attention in the market. All operations are structured feudally around one author or two authors as the master smiths. There may be grander unity and divisions between them all – the CoPub and the trad-turned-NewPub. Periodically an operation collapses, or wordslingers cross from one side to the other – much like the Sengoku Period or the current personality politics of Japan.[21]

Logic suggests that both these types of fiefdoms – will use the Amazon model and work similar to record labels founded by rappers[22] and Led Zeppelin.[23] The CoPubs are likely to have an advantage in terms of speed, which plays a significant role in the algorithms of the Amazon model. The NewPubs will have an advantage in advertising due to sheer brand power. Both will stay relatively small and agile.

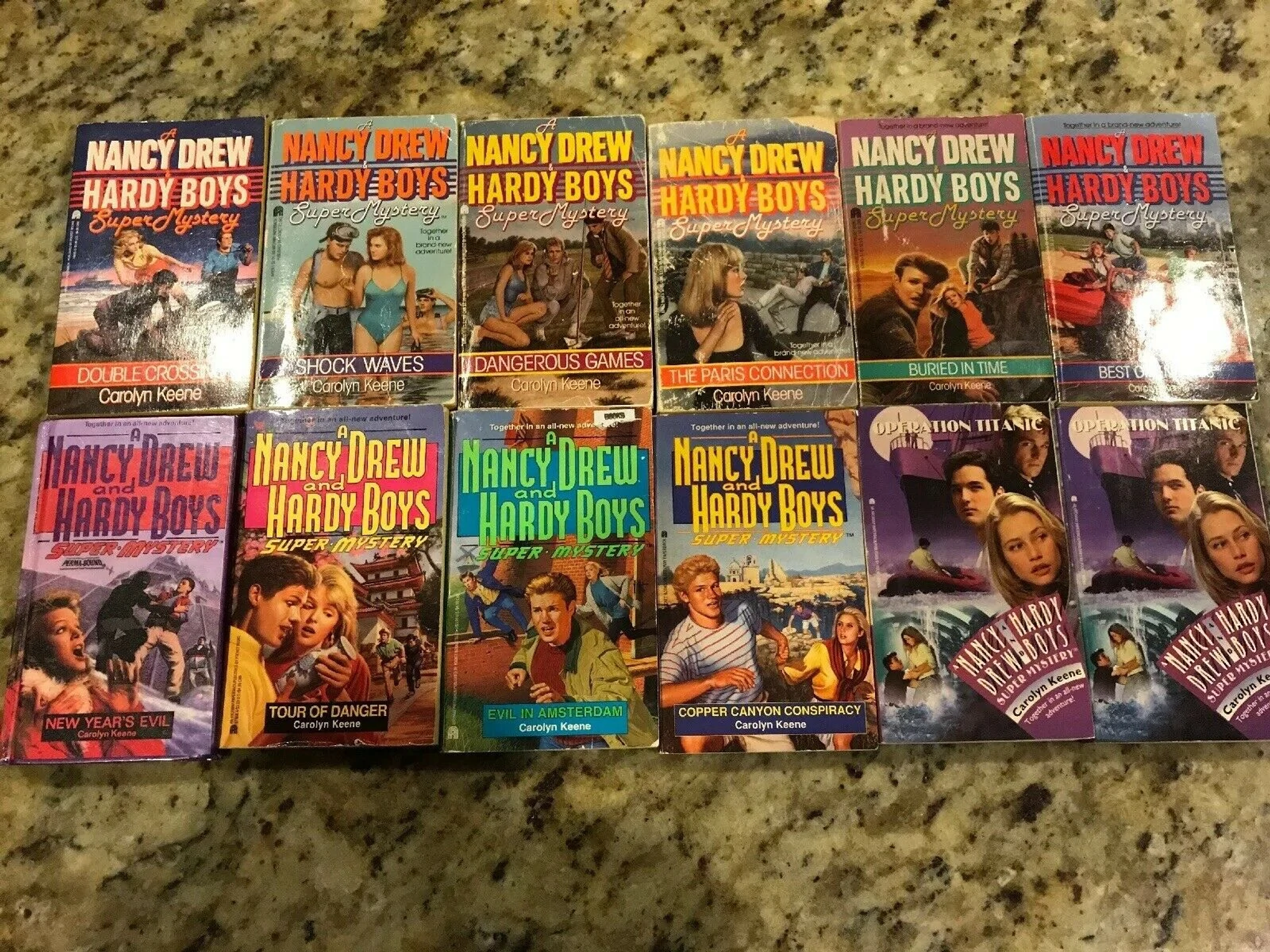

What of ghostwriters? Ghostwriting is significant business. Growing up, I first became aware of it in K.A. Applegate’s Animorphs series – I later learned that the author had a very structured process where they outlined books and had ghostwriters do the work.[24] I later realized the same thing held true for Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew, produced by the Stratmeyer Syndicate in the 1930s.[25]

Obviously this exists and might last as long as markets exist. But we have no way of identifying them[26], and so have chosen not to talk about them in the analysis. It’s my guess that they’ll mimic the structure of CoPubs.

What of the TradPub model? We believe mid-sized TradPub will suffer, but the Big Five may be “too big to fail”[27]. The allure of the mainstream publishing contract is a powerful thing. After all, not all authors are profit-driven, and in the model of the attention economy there are other ways we reap satisfaction from our work – prizes, honors, awards and such prestige are social capital and thus will likely always be largely tied to Big Five publishing.

In an optimistic future competition forces them to give their authors a larger share of the royalties and focus more on digital.

We don’t know if this will happen. Big Five publishers appear to diversifying their operations by investing in smaller presses.[28] The authors still make pennies, but this provides an excellent feeder network where editors with taste and niche knowledge carefully curate massive quantities of books, and something eventually goes viral, at which point the Big Five’s marketing budgets kick in and a new star is born. Moreover, it makes it easier to shut-down non-performing presses. TradPub may be taking lessons from the mammals, but we’ll have to see if benefits trickle down to the authors.

Meanwhile: bring on the fiefdoms. More competition is a good thing. Even if one doesn’t want to set up a franchise, the fact that these avenues now exist is great for all authors.

If there is a counter-narrative to these trends I’ve highlighted, please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below. The more data we have, the better.

[3] https://www.pw.org/content/notable_moments_in_selfpublishing_history_a_timeline

[4] https://almossawi.com/big-five-publishers/

[5] https://electricliterature.com/how-indie-presses-are-elevating-the-publishing-world-deb06dc11c8a

[6] https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/what-is-meatspace

[10] Murger, Scènes de la vie de bohème, 1851; Virginia Nicholson, Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900–1939

[11] https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2019-01-14-franchises-are-the-endgame-opinion

[13] http://blog.tavbooks.com/?p=226

[14] https://www.avclub.com/pay-no-attention-to-the-man-behind-the-curtain-7-ficti-1798239907

[15] https://lmbpn.com/

[16] https://sterlingandstone.net/about-sterling-and-stone/

[17] http://www.waterhousepress.com/

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dunbar’s_number

[19] “…in an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it” – Herbert Simon, 1971

[21] https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2001/08/personality-politics-conquers-japan/377730/

[22] http://www.xxlmag.com/news/2016/08/rappers-record-labels/

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swan_Song_Records

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animorphs#Ghostwriters

[25] https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/05/hardy-boys-nancy-drew-ghostwriters/394022/

[26] To confound the analysis, many people write under pen names in the industry – from Bella Forrest (who nobody seems to know) to James SA Corey of Expanse fame, who are actually Ty Frank and Daniel Abraham.