The fate of the gorillas

A few simple thoughts on superintelligence, synthesizers, perception of value and also gorillas.

I would like to propose a very basic framework. I would like to propose that there are basically two types of intelligence that threaten humanity.

1) Faster intelligence. 2) Stranger Intelligence.

Faster intelligence is essentially what we can conceivably do by ourselves, only sped up significantly. To a great extent, much of modern computing is fast intelligence. Early computers were sold on the promise that yes, you could do calculations and accounts by hand, but this could do it faster for you. You can learn to paint and create a masterpiece by hand, but Photoshop will get you there faster.

Large language models, which are one of the key ingredients in the public perception of AI today, are faster intelligence. They are essentially a personal intern sped up several thousand times. Yes, given enough effort, you can learn to write that cover letter, and you can probably do a better job. But this helpful automated intern will brainstorm it with you and arrive at several dozen outputs in a fraction of a fraction of the time. Likewise, for pair programming: you can debug on your own. But in the time it makes you to fix a cup of coffee for yourself, this thing can read your code base and point you in helpful directions.

Faster intelligence is easy to identify, easy to quantify, and thus easy to sell. It’s fidelity lies in how close it can get to being a human like intelligence, only significantly faster and thus, significantly cheaper to the end user.

Faster intelligence is also easier for us to understand because ultimately it is us sped up. Minsky’s definitions of an algorithm apply here. It can be achieved with someone with pen and paper and a hell of a lot of patience. The problem that it chiefly solves is not one of intelligence but of time.

image by Cottonbro on Pexels

image by Cottonbro on Pexels

When I was in school, I studied mathematics. In our class was a fellow who could do much of pure mathematical operations entirely in his head significantly faster than we could on paper. This did not make him a better mathematician. Complex multi-part questions would routinely stump him, and ultimately he did no better than any of us on the exams. But I remember that feeling that I got when meeting him for the first time. It was a feeling of, wow, this guy has to be really smart. He’s so much faster than I am. He’s top of the class for sure.

This is the same impression that we get when interfacing with a particularly competent large language model. That this is us, but faster.

Let’s try and apply this thinking to what we call AI today. As I write this, the leading contenders for the throne of “artificial intelligence” are some flavor of large language model.

Much has been made of their utility. This is largely speculation, of course, but first impressions in many fields have seem to have convinced people that these will take over the world and do so many of the tasks that interns and entry-level knowledge workers are typically hired to do.

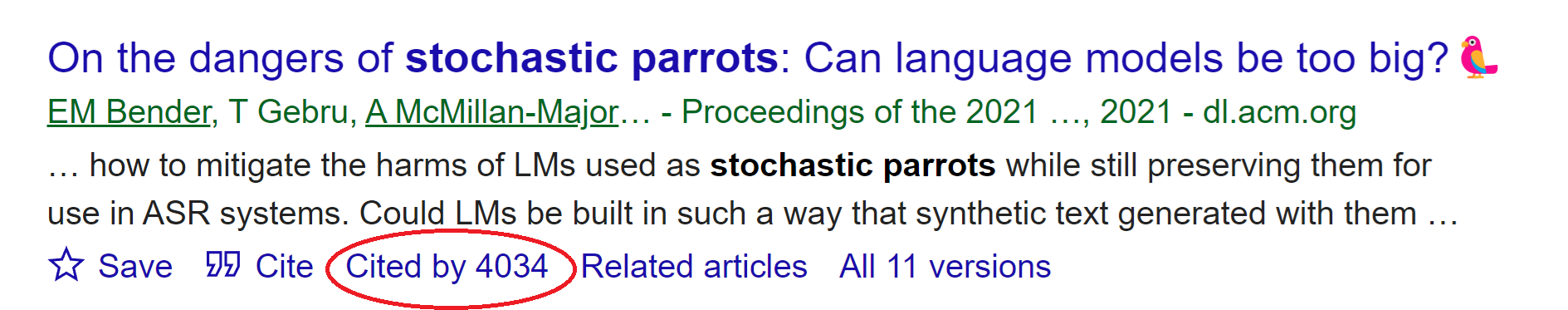

And then, of course, there has been the more philosophical angle. If something appears to exhibit some level of human-like reasoning, is it intelligent? Has it somehow through language absorbed some kind of facts and knowledge about the world? Has it built a map of the world and its meanings in its gguf file of a head? Is it just a Chinese room, a bunch of heuristics stapled together that can give the impression of convincing conversation without any actual thought inside? Aren’t these models just sophisticated stochastic parrots?

And then as the technology profilterated from consumers who saw themselves being on the receiving end of these technologies. And with them there is this underlying question: is this useful technology in the first place?

The practical answer seems to a little bit of column A, a little bit of column B. Leaving side the ethics of data collection just for the sake of simplifying this argument - I’ll get to that in eventual post. There’s been ample evidence that a question is not all that it is expected to be. The Silicon Valley executives have typed this as the grand be-all-end-all ultimate labor replacement. And yet in many fields where it has been deployed, we have seen that AI systems without immense degrees of control, customization and research are not at all reliable enough to be used in many of the activities, the world considers necessary to go around.

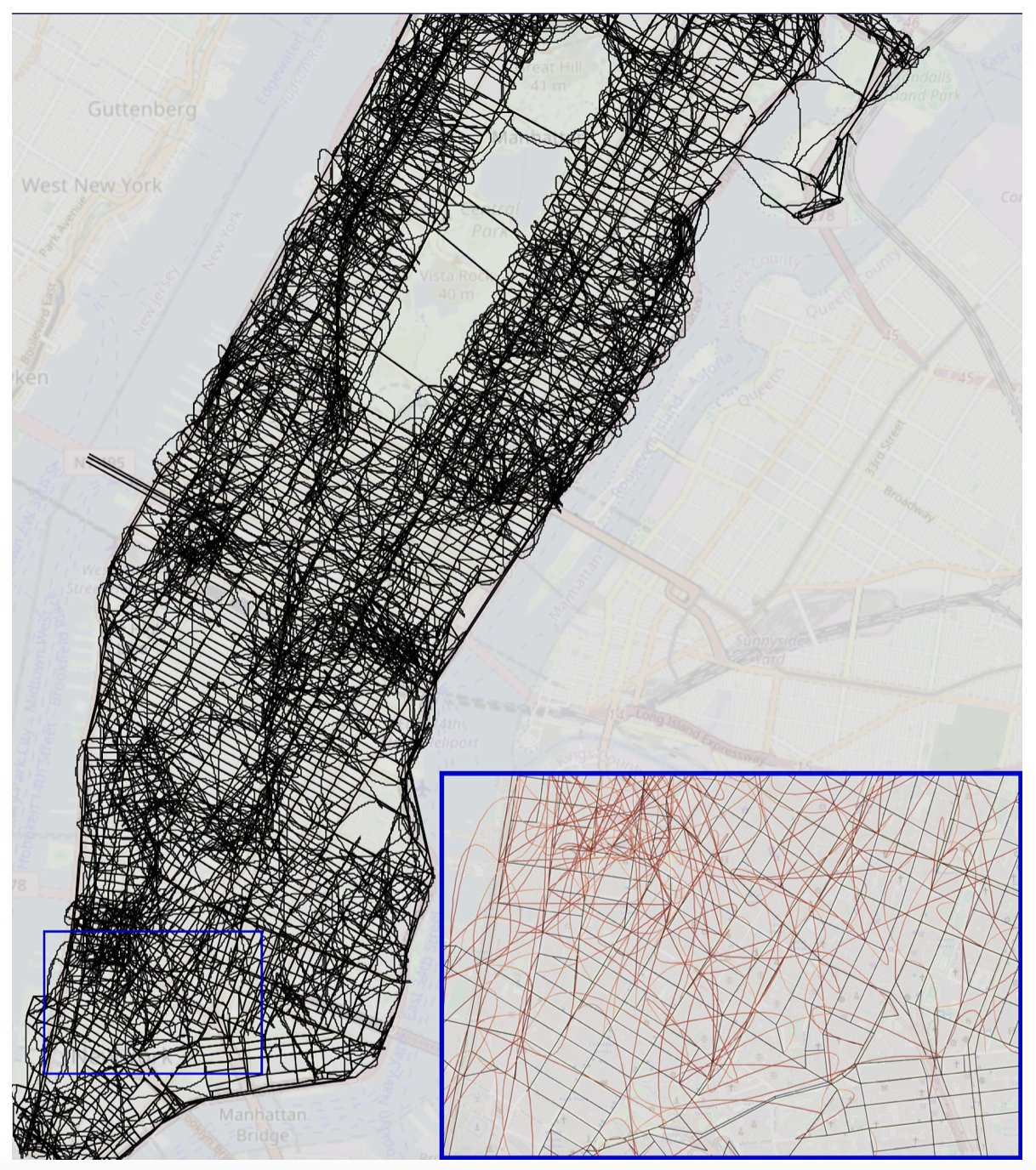

At the same time, in more localized examples we find plenty of programmers whose lives have become a little bit easier when dealing with the muckwork of programming: converting code between languages, getting started with those first bits of scaffolding code, debugging, commenting. One particular use case that I find genuinely interesting is in learning; I’ve saved myself several hours of simple configuration problems by describing my problem and asking for a tutorial for that specific problem.

Inasmuch as there is intelligence here it is of that faster intelligence sort: it is the equivalent of asking some people with a lot more time on their hands than i do to help me fix a very specific problem. The AI model in this case is fast, but it is not necessarily very good. While for trivial, oft-repeated tasks, the model may indeed be better than I am, get into the weeds of a complex problem and you find it showing its ass, more often than not. You find it clawing itself into very bizarre bits that it simply cannot think its way out of because ultimately it cannot really think.

Its strength lies in its speed and the commonality of the task, not in its first-principles thinking.

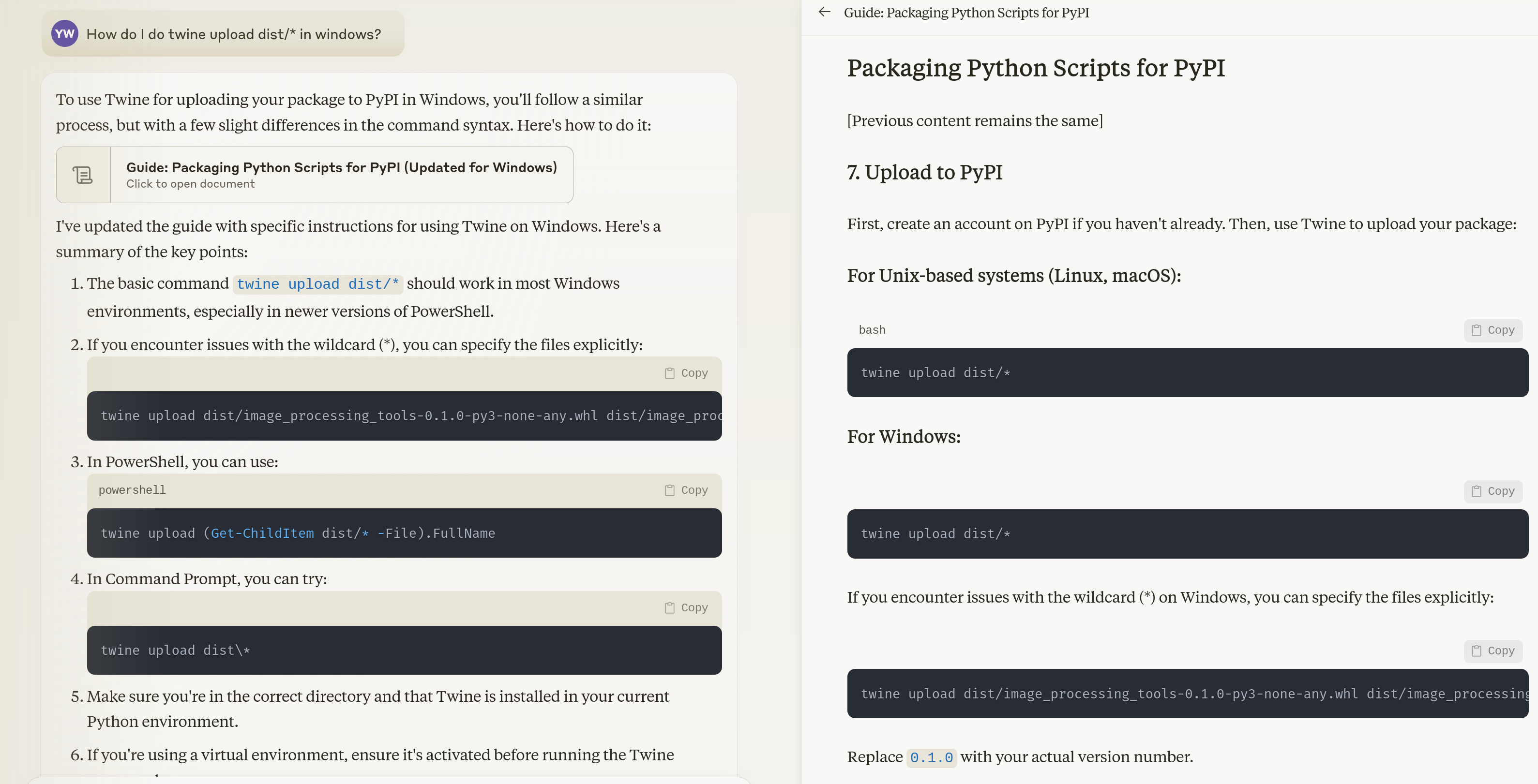

Let’s look at an example from a different domain. I’m going to pull up the work of Vafa et al, who trained a transformer model to estimate trips in New York City. The model’s predictions were, in their words, quite accurate. Great! But when they deconstructed the map of New York that the model held in its world, what they found was this strange thing underneath.

Vafa et al’s paper, “Evaluating the World Model Implicit in a Generative Model”, is worth a read. What it demonstrates is how flawed the underlying world model of this current generation of intelligence is. Even if it appears to mimic intelligence, even if it can fool the stupidest among us, or write better poetry than the worst poets on Instagram, it does not truly understand the world around it. And Vafa et al., whose research questions give these types of models more credibility than just stochastic parrots, conclude ultimately that underneath is just pure nonsense.

What we have here is an example of faster intelligence. Indeed, its chief utility to us, insofar as the venture capital pitches or the marketing PR goes, is that it can perform a task faster than the intern you just put on payroll. Will it be more accurate? Will it learn? Will it be able to use tenuous data points to demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of the world? Certainly not. But it can throw many tomatoes at the wall until something sticks.

This is just intelligence of quantity, not quality. Western countries have over the past so many decades made tremendous use of intelligence of quantity, particularly by underpaying workers in countries like mine. It’s shit work, but we do it cheaper and faster, and therefore you can have 200 Indian or Sri Lankan employees paid a fraction of what you would pay a Silicon Valley engineer. To those cheap employees, you give the work that you do not really want to do: manufacturing garments, annotating data, translating articles on Mechanical Turk. And you reserve the highly paid engineer for everything else.

This does not offer us new insights. All it gives us is more and cheaper labor.

Stranger intelligence is a little more difficult to capture. Fundamentally, stranger intelligence allows us to look at things in ways we haven’t been able to do before.

Stranger intelligence is hard to explain because there are very few examples of it being made as a different type of intelligence. Stranger intelligence usually emerges. It is an emergent function of multiple types of faster intelligence interacting with innovations in between different layers and frameworks of operation that slowly lead to incremental upgrades to capabilities that eventually result in something spectacular and terrifying being brought together.

I’m going to propose four examples here in what I see as increasing degrees of sophistication. The first is the press. The second is the Moog synthesizer. The third is telephony; the fourth is social media.

The Gutenberg Press revolutionized the acquisition of knowledge and the spread of culture. In making books mass produced objects, not only did it vastly empower the spread of religion (and with it, massive expansionist empires powered by the first true multinational corporate armies), but it also greatly accelerated the sciences and the arts. Books became not just decorative objects for the ultra wealthy, but commonplace manuals of instruction for pretty much everyone. It enabled education systems that have put ideas and facts into more people’s heads than ever before in human history. It created careers an objects that had scarcely existed before: from the bestselling author of platitudes to the modern day journalist to the textbooks that we use in schools and colleges to the journals in which we publish academic literature. Of course, a few monks who had spent years painstakingly hand copying and illustrating editions of the Bible got the short shrift, but civilization prospered.

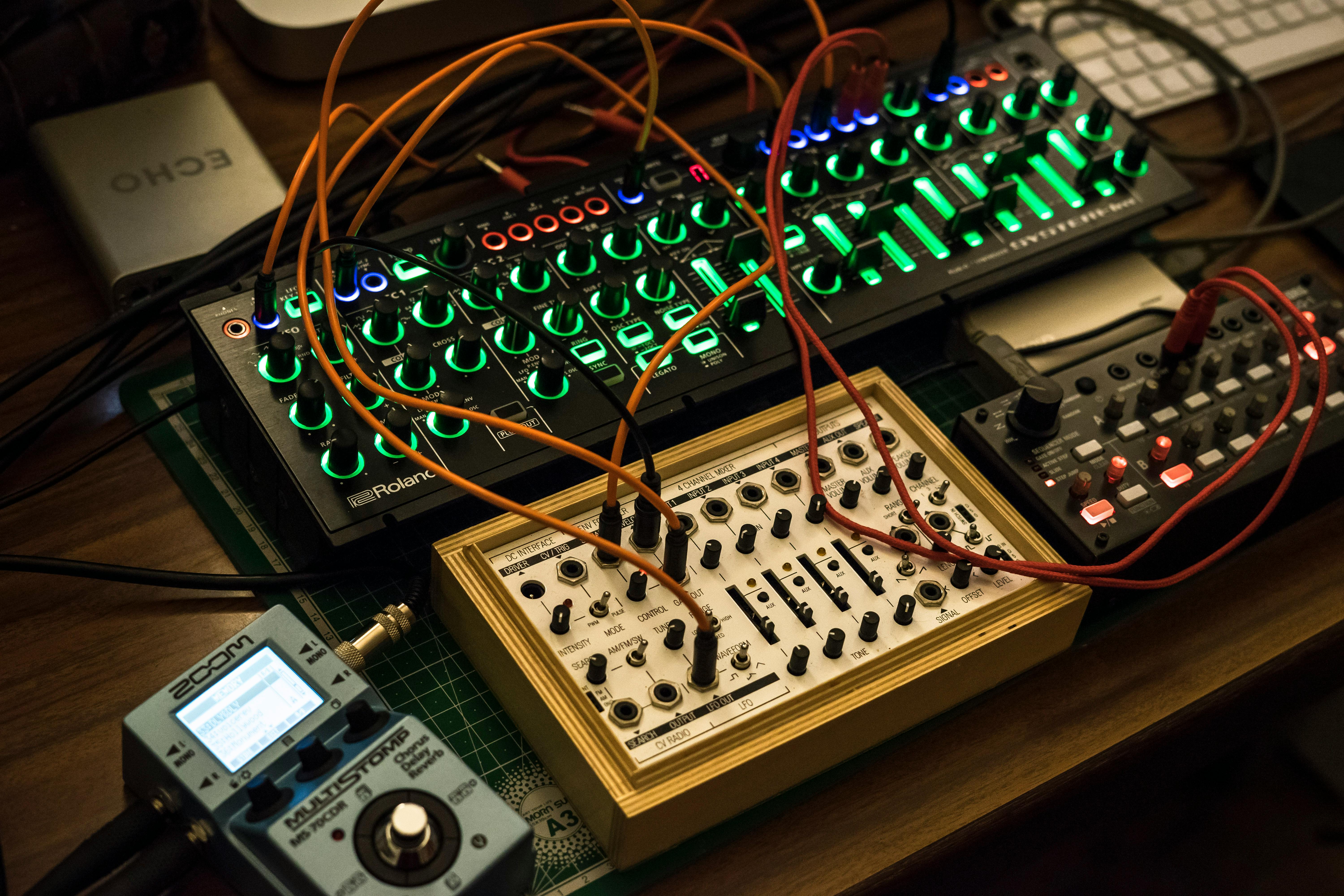

When the Moog synthesizer was first released, there was outcry from musicians to the extent that it was banned for a period. Its original creator envisioned samples and recordings of musical instruments being worked on in different ways. But I doubt that Moog himself could have foreseen the rise of EDM or the eventual integration of almost all popular music with the synthesizer.

Image by Carlos Santos on Pexels

Image by Carlos Santos on Pexels

Even further afield would have been Fruity Loops, the licensing of music packs and effects and tunes and the variety of careers around these things, and the rise of Mongolian throat singers producing exceptionally popular music on YouTube.

Telephony is another such example. Once the telephone became widespread, and particularly once it became mobile, we as a species were allowed a degree of communication hitherto unimagined even by the most powerful and power-hungry of prophets and kings.

Many projects in human history have reduced the distances between us. The press, the telegram and radio are but a few. But telephony was an explosion in many to many connection around the world. It forever changed the shape of not just business but of how we communicate with each other. Our language, even the word hello is an introduction from this technology.

And then there is social media.

(I should really say the internet. But social media, I think, can be seen as the tip of the spear. And in many of our countries, it is. In national representative surveys conducted by LIRNEasia, where I used to worlk, we noticed that in countries in the global south, people may say that they do not have Internet. They do not even know what the Internet is, but they do have access to Facebook. So whether we like it or not, social media has become one of the dominant faces of the internet as a whole.)

But I digress. The impact of social media was goes far beyond what was originally envisioned, even by its own creators. Not only did it slowly erode institutions of communication, but it turned every single human being with access to it into a potential broadcaster in their own right. Intertwined with every potential piece of misinformation out there were entirely new forms of business entirely new forms of community entirely new ways of sharing empathy and stories and art culture shifted forming into memecomplexes that are global in nature, beyond the ability of any nation state to regulate.

These things ultimately give us new ways of thinking about the world. They are not, in and of themselves, efforts that we can imagine by just thinking of ourselves sped up by five hundred fold. The repercussions of strange intelligence, or what these things can grow to be, is not immediately apparent from the onset. They need to interact with many other things with other advances, sometimes coming from completely different fields, sometimes coming from tangential innovations to present some glimmer of promise.

Occasionally some part of the fabric of these things envisioned in science fiction, just as such virtual environments are envisioned in Neuromancer or Ready Player One, or even Ender’s Game. But the this envisioning is no more than a rough dream of the future. This is the nature of the ingredients for strange intelligence. Its initial envisionings are only a tiny portion of the picture, and eventually things come to be that something special emerges. In person, strange intelligence often looks like a strange weed until it merges with some other plant to produce a mighty tree.

What might superintelligence look like? Well, this is the useful question that we get to.

To a great degree we say superintelligence can exist because it must exist; because it is hubris to believe that human intelligence is the top of the pack.

But what does it look like? In a strict sense it is an impossible question to answer because first we need a test for intelligence. We have no concrete theory of mind. And without a theory of mind, any system - now or in the future - could either be just a Chinese room or indeed a super intelligent entity that we fail to recognize as such.

We wave around the Turing test sometimes, but the Turing test has been obsolete for a long time. In fact, it was obsolete with ELIZA in the 60s, and today it can only be used as a test of naive humans. Even if you do design an updated test, there is always the danger that a stranger superintelligence may not even register, while faster intelligence obviously aces it without effort.

Our quest to understand intelligence is also polluted by our history as tool users. Throughout human history, we have domesticated, bred and used for meat animals of varying degrees of intelligence. We regarded them as tools. We have also extended the same attitude towards other human beings. When we say we are looking for superintelligence, we are biased observers, because we tend not to acknowledge intelligence in others if we can subjugate them to the level of tools.

A machine capable of intelligent thought, if it was no smarter than a cat or a dog would be treated as we treat those animals. A machine capable of superintelligent thought, even if it could think thoughts far beyond ourselves, we would treat simply as a tool as long as we have access to the on/off button.

I used to believe that we could examine intelligence by first examining how a creature faces its own death. That is to say, how it reacts to a stimulus that suggests the end of its own existence. However, even the most complex and ritualistic of behavior concerning death has often been dismissed as mere savagery, even when the participants in the conversation are almost identical. So this is not a fruitful line of thinking.

But for the sake of conversation, let us assume that superintelligence can be demonstrated and that humans can be convinced that something is superintelligent.

I believe that superintelligence lies at the intersection of faster intelligence and stranger intelligence. We are using these concepts here as a Wittgenstein’s ladder to describe something that is faster at our line of thought than we are, and at the same time is capable of reacting to stimuli in novel and complex ways that we cannot imagine or fathom. When you put these two together, what you get is a system that moves far faster than we can, but is also not completely predictable in what it may favor or condemn.

Are there examples of superintelligence around us?

Nick Bostrom, who is one of the stalwarts of the of this field of thinking, wrote:

The human brain has some capabilities that the brains of other animals lack. It is to these distinctive capabilities that our species owes its dominant position. Other animals have stronger muscles or sharper claws, but we have cleverer brains.

If machine brains one day come to surpass human brains in general intelligence, then this new superintelligence could become very powerful. As the fate of the gorillas now depends more on us humans than on the gorillas themselves, so the fate of our species then would come to depend on the actions of the machine superintelligence.

But we have one advantage: we get to make the first move. Will it be possible to construct a seed AI or otherwise to engineer initial conditions so as to make an intelligence explosion survivable? How could one achieve a controlled detonation?

Image by Pierre Lescot, from Pexels

Image by Pierre Lescot, from Pexels

The fate of the gorillas here is an interesting thing to contemplate. This definition of intelligence presents intelligence as power exerted in the material world. To a gorilla, humans are mysterious creatures, appearing perhaps individually weak and unworthy, but collectively phenomenal threat that it cannot escape from, a fence that rings around its world no matter where it looks.

And importantly, we humans control the on/off button.

What is to us as we are to gorillas? By that account, the reigning contender for superintelligence is our current economic order. It is composed of many processes, the output of which collectively is far beyond the capability of humans to process and decipher.

We make rationalizations after the fact and every economist can cobble together an analysis of how some country collapsed and so on and so forth. But the fact remains that the individual processes at play are far too complex and far too vast to ever comprehend.

In Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia, the child genius Thomasina makes the following observation:

If you could stop every atom in its position and direction, and if your mind could comprehend all the actions thus suspended, then if you were really, really good at algebra you could write the formula for all the future; and although nobody can be so clever as to do it, the formula must exist just as if one could.

This does not apply to just the universe itself but also to our economic order. There is nobody capable of comprehending all actions within this system of systems and of writing an algebra that could provide the formula for the future. At best, we work with simplified models and rationalized arguments operating in reduced dimensions, and then collectively panic as the system turns out an output that we do not expect. Today’s careful well-ordered policy with well calculated risk is tomorrow’s market failure; today’s predictive pundit is tomorrow’s laughing stock.

The economic system as a whole is faster intelligence in that it is much faster than we can comprehend. It is also stranger intelligence in that some of its outputs are not things that we can understand readily. Many powerful players operating at nation state levels, and at the level of multinational companies, attempt to exert significant influence on it, but even they must bow to market shocks and disruptions - and the latter by nature, is unpredictable except on level that borders on faith.

Another system that I would like to put into this category is nature. The collective noun is a bit of a misnomer. Nature is an incredibly complex system of systems that again, we are not even remotely close to modeling understanding and being able to predict. Humanity has fought with, attempted to subjugate, destroyed, and attempted to resurrect nature in so many instances over so many millennia. We may have sophisticated satellite imagery and very complex models that allow us to simulate weather; and yet we do not have an on/off switch; even our ability to get out of the way is extremely limited.

We may look at these systems and laugh and say there is no intelligence there. But consider how much knowledge is even required to approximate even a simple understanding of any of these systems. Consider the effects on our everyday lives. Consider how they control ultimately the fate of not just you and me but entire nations.

Do also consider that despite initial appearances, they do contain intelligent components. Indeed, something like the economy is really a vast conglomeration of such intelligent components: from the shopkeeper who runs a little store down the road to the most sophisticated hedge fund to various conferences of central bankers and IMF executives. We must even reluctantly consider day traders as intelligent units of this whole system; almost individual neurons in a gigantic and very confusing globally distributed brain. The same can be said of nature. After all, despite it pre-existing us, humanity has had an outsized impact on it.

These systems are humans and we are the gorillas. By that definition of being able to exert power in the physical world, they are indeed superintelligence.

I have presented here one system that is artificial and one that is natural. One is self made; GDP is not a naturally recurring, occurring element. And although we cannot claim today that nature exists independent of us, it is certainly more powerful a force than we are. We do not collectively possess the on/off button here.

How then do we identify other intelligences that might emerge?

The present day AI conversation is disconcertingly obsessed with tasks that we think of as human. Personal assistants, calculators, pair programmers - what we are building faster versions of what we already do, because it is useful for us to do so.

The lens through which we judge the promises of something are typically through work and of productivity. This is not a uniquely capitalist feature. Socialism and other systems, too, have constraints by which they judge work, functions of utility. As long as the product is work, we will only create things that let us do faster work, and we will laud it only in its capacity to do so.

The self-driving car is, after all, a fundamentally faster horse and carriage, and that is a more efficient palanquin. It exists to satisfy the requirement of moving humans from one point to another; we have just progressively replaced more humans in the picture.

Perhaps a simple question would be to ask how can it change play? Play is often ignored when we ask questions of progress. And yet it is a critical component of why we have GPUs, K-pop bands with holographic effects, drones that can cover both weddings and war fronts, AlphaGO, and jewelry that often incorporate a small medical lab’s worth of sensors.

It is when someone decides to make a better computer for the sole purpose of playing more realistic games and that hardware turns out to drive a great leap forward in scientific computing that we end up with some glimmer of super-intelligence.

A more serious example would be ideologies that evolve in backroom chat channels and combine with international shipping and logistics and cash and credit to eventually turn into a series of violent deaths inflicted upon innocents. Something has emerged that is beyond our collective ability to model, predict, or really control. Again: a spark of superintelligence.

Sparks of AGI, if you will allow the pun. Maybe our best way to identify superintelligence is not by trying to create a scientific definition of what is and what is not, but to identify repeating paths through which these kinds of sparks appear, on the basis that one of them might lead to something.

And yes, sure, work may get us there. Endlessly trying to create another analog of a human intern, we may discover an extraordinarily wasteful, compute-intensive way of digitally doing what people have been doing for a very long time - producing babies, teaching them, letting them work their way through the world. But for my money, I think play is what’s going to give us those more interesting moments: not work.

Tielhard de Chardin theorized of omega point: a moment at which humanity’s collective evolution as a civilization and as a species combined with nature and all the systems present therein, is unified into some sort of super-being. He saw this as the ultimate march from inanimate matter to some sort of divine consciousness.

Granted, his understanding of thermodynamics might seem a little shaky. He had some interesting opinions on humanity and the heat death of the universe. And he may have been overly optimistic about us merging into some sort of unified super being; clearly, Twitter had yet to be invented in his time. However, this Teilhardian singularity has often been mirrored in discussions of a runaway intelligence explosion that will lead to a superintelligent being.

There never may be an omega point. I think such a nexus can only exist in the most simplified models of the world. But instead, there are millions of small omega points in which many systems - unexplainable, unpredictable - combine to create some unique moment, some zeitgeist. And some of these omega points may actually turn into pathways that enable systems that ultimately cannot be controlled and are to us as we are to the gorillas, and that fundamentally shapes our future going forward.

I believe the fate of the gorillas rests on how humans play. I believe that, as the gorillas in the picture, our fate rests on what we create while we play and how these things connect and what they might unfold. I do not believe that we can predict superintelligence, but we can in the least steer it away from what we fear.

Here are omega points that we may wish to avoid:

1) omega points that wish death upon the living. 2) omega points that trivialize human dignity and the fundamental rights that we have come to embrace. 3) omega points that seeks to void the social contracts that allow us to have these thoughts and conversations in the first place; such a superintelligence stemming the free flow of ideas would seek to be the last superintelligence. 4) omega points that take agency away from humans and places it in the hands of entities for whom humans have no liability, responsibility towards or accountability for. 5) omega points that seek to place the fundamental resources of our world - that is energy, food, water, shelter - and place them in the hands of a few.

There may be more such omega points. This is not an exhaustive argument and nor is this an exhaustive list. I am after all also presenting a very simple model of the universe here, and indulging in a lot of wandering rumination in the process.

But I believe that, as the gorillas in the picture, our fate rests on what we create while we play and how these things connect and what they might unfold. I do not believe that we can predict superintelligence, but we should in the least be able to detect whether something is triggering some unsafe omega point.

To do any less would be to consistently confine ourselves to being in a zoo, with something else holding the on-off switch.

As I have said, this is merely a sequence of simple thoughts. There is no sophisticated thinking here. Finally, after all this rambling, we get down to the real topic at hand, which is are we creating more superintelligences? And how do we prevent superintelligence from owning that on/off switch?

This inevitably treads on the problems that I have been involved in over the last so many years, but hate to talk about; regulation, public policy, state capacity.

There is one way, which is to tally up all the ways that things could be dangerous and preemptively block or ban them.

This is not my favorite approach. I am no American gun rights fundamentalist, but this argument of “X could be dangerous has been used often”, particularly in countries like mine, to erode fundamental freedoms and prevent the spread of technologies that give power to citizens.

For example, it is the exact same argument that generations of Sri Lankan presidents have used to block social media whenever they or their political allies are getting slandered for corruption. I actually do have a Supreme Court case lodged against a former president for this very particular thing, and their argument was that social media posting somehow compromised national security. These types of arguments may seem ridiculous, and indeed they; but when a method of preemptive blocking and banning and when such culture is baked into law, this is the only outcome.

The second approach, which has been the default public policy approach, is to instigate rules after the fact. After some observable harm has been done, rules are set in place to make sure it does not happen again. OSHA regulations are a good example of this.

This means that rules and regulations typically tend to be written in blood. This is also a painful approach. Recent reading led me to Brian Merchant’s Blood in the Machine, in which he details the story of Luddites. It is clear that regulation arrived only after a generation of children had been tortured, maimed and their fingers crushed in factories and the character of life forever changed.

This approach of regulating after massive public outcry translates into political expression by representatives may have worked when technological spread was slow, but as I have pointed out with my examples, we have had many generations of technologies that have brought us closer, reducing the distance between the spread of ideas. Every generation of new technology tends to acquire user bases much faster than the ones before. We can expect both the damage and the benefits to scale appropriately. In many cases we can expect these to be underway before the representatives even wrap their heads around the existence of the technology.

The middle path is to see whether there are experiments that can be run that preemptively do demonstrate harm, with instruments, simulations, testers and/or volunteers. Certifications are then assigned.

This is how drugs are tested. We do this for all manner of things. Computer mice have certifications.

To an extent, this does clash with how we think about corporations in the modern world. Many corporations, particularly those of a software-based nature, are given extraordinary license to move fast and break things. And yet, just as we expect people, when they break things, to apologize and make amends, we should also be able to hold corporations accountable for breaking things. The potential breakage could be tested beforehand to make it fairer for everyone involved.

This is an approach of cautious conservatism. It tries to strike a balance between clutching pearls and mopping up the blood after the fact. It is the principle of looking before leaping.

It is also not perfect. There is of course an argument that this kind of regulation only strengthens the incumbents who have had enough time to solidify their position. And yet we force people to take driving tests to certify that they are safe enough to be on the road. Certainly, people who have been driving for a long time find these tests much easier to pass, and no doubt quite a few young drivers are frustrated, but on the whole it makes society safer.

There is also the argument that this sort of testing requires extraordinary capacity in government. This kind of capacity is genuinely hard to build; after all today’s technological progress is rapid and many of those most eminently qualified are lured by expensive salaries to the all-important task of optimizing click-through rates on an ad for mystic yoga moms. Much of other progress happens in open source spaces, where progress and ideas and contributions are massively decentralized and nearly impossible to contain. And if we are serious about super-intelligence, we have to acknowledge the fact that we really need extraordinary capacity to maintain oversight of the intersections of strange and fast intelligence and see if they lead somewhere.

What then do we do? Do we adopt a policy of blind trust, letting brave, greedy and sometimes foolish pioneers blunder into the wilderness and hoping that nothing comes back out of it to slaughter us? Do we stay within our homes forever, afraid of the world outside? Do we meditate on every road in the garden of forking paths before moving a foot?

This is the fundamental challenge facing us today. We face the concept of superintelligence but have no real conception of how to define it. Even having defined it (in however haphazard a manner as I have done here), we still need to make hard choices about how we go forward. No choice here is universally pleasing. And most damnably, we still don’t seem to have a decent way of identifying superintelligence, let alone regulating it.

This construct of the driving test is key. The driving test, unlike an FDA drug trial, is not so expensive that only corporations with massive millions can afford it. It is cheap enough and easy enough to implement that it is a reliable, reasonably usable test. Even governments and regulatory authorities without much in the way of resources can enact it.

What, then, is a driving test for something that we may only identify after the fact? What is the simplest sequence of processes for identifying an omega point and tracing back its causes and trying to understand what here might be super intelligent?

This is where I must end my thoughts and leave it in your hands. To some degree I believe this lies on our conception of omega points as I have outlined them above.

Technologies may move faster than we are capable of comprehending, but the fundamental needs of humans have moved much slower. The Declaration of Human Rights does not change with every Twitter hot take. Our general conception of things that we need to improve about the human condition have probably not changed a lot either. The UN SDGs, as uselessly broad as they are, are proof that we can at least agree on a few lines of text; perhaps with enough tinkering, we may get to a list of desired outputs.

Perhaps these can form the principles for the outputs that we desire or dislike.

Hopefully this has sparked some train of thought. My apologies for the shoddy construction of the station, but I hope it serves well enough to get the train rolling.

On account of a broken hand, this post has been written using Whisper voice-to-text; AI.