Watchdog Sri Lanka

A factchecker, data journalism operation, public software builder, an open-source research collective.

In which my poetry generator and fiction ended up on the Moon, thanks to Samuel Peralta's efforts to build an archive of art.

This is a very odd story. This is how an experiment - a poetrybot - made it first into two books, and then to the moon.

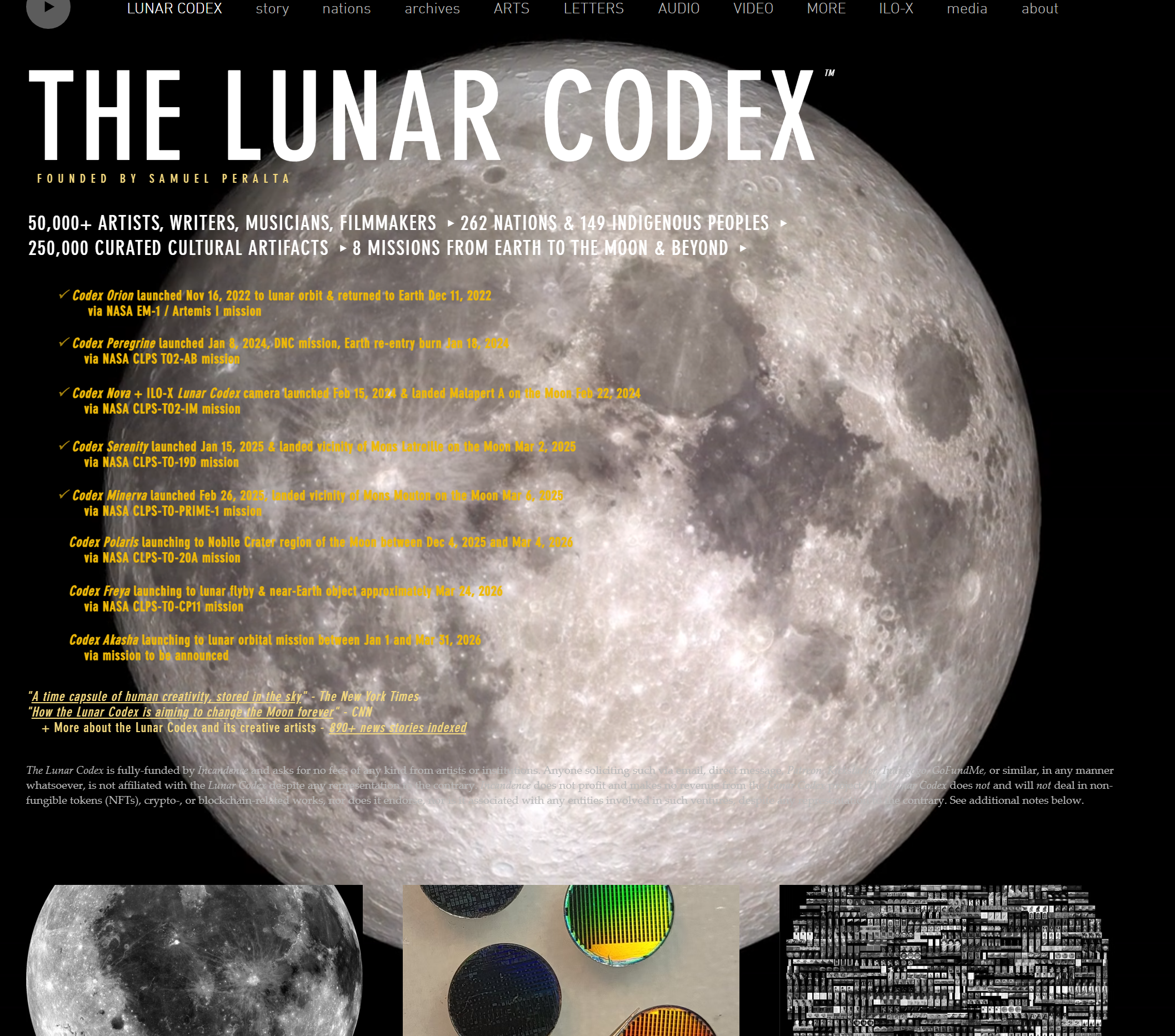

Why the Moon? Because of a project called the Lunar Codex, spearheaded by a friend of mine - Dr. Samuel Peralta. The New York Times article does a good job of explaining his one-of-a-kind archive: works from tens of thousands of artists, parked on the actual Moon via lunar landers and missions that involve everyone from NASA to SpaceX to Astrobotica.

Neil Armstrong’s footprint, it is said, will last at least a few million years. Conceivably a digital archive of works will last a longer, so eventually, when everything we have said and done are dust and ashes, someone will open it up. Maybe it’ll be a new species of human; or a machine; or an alien. Whatever it is, among those works will be a few of mine:

-Megastructures - the anthology that I edited and published -An early protoype of Claws and Effect, in the form of a short story that covers the first chapter, published as part of the Hellcats anthologies by Magpie Lane -A short story in Samuel Peralta’s “Chronicle Worlds: Crime and Punishment”, expanding on the world of the Writing Contest and Beatnik -AND the star of this particular piece: poetry by OSUN.

Let me write down the personal story of how we got here.

A screenshot of the Lunar Codex page.

A screenshot of the Lunar Codex page.

In 2019, OpenAI released a large language model called GPT-2. The original blogpost) and its attendant paper were pretty big deals, but more or less in the tech community and among journalists. Even the portion of academia that pays attention to natural language processing and machine learning looked at it, basically thought it was cool but overhyped, and generally went back to what they were doing.

I happen to be working right in that field, working on corpora, stemmers, lemmatizers - the bread and butter of language processing. At this point I was working on the language overview paper with Nisansa; I wanted to try my hand at something more complex. And this looked like a cool toy; despite OpenAI’s statements about how it could be used for misinformation and all that, what I saw mostly was a weird, quirky thing that was delightful precisely because its output was so strange and inhuman sometimes.

Intrigued, I downloaded the weights of the GPT-2 model. First 117M, then the larger sizes. I learned the laborious process of fine-tuning this thing on my laptop (which, poor thing, suffered). On that note, fuck you, Tensorflow. Anyway. I concocted and carried out a few experiments. Then published this post on Medium; it ended up on Towards Data Science:

I’ve always admired the translations of Chinese poetry – I’m no expert on the field, but there are two poets named Du Fu and Li Bai that I _really_ like. They were legendary masters from the Great Tang Dynasty, and (if the translations are accurate), they had a phenomenal talent for freezing a moment and capturing that particular slice of time with their words; their poems read like a string of Polaroids stretched across a riverbank.

Here, for example, is a Du Fu poem. Among other things, there’s a certain simplicity here: one strong emotion resonates through, and unlike much of the English verse I grew up with, it’s firmly in the present tense:

A LONG CLIMB

In a sharp gale from the wide sky apes are whimpering,

Birds are flying homeward over the clear lake and white sand,

Leaves are dropping down like the spray of a waterfall,

While I watch the long river always rolling on.

I have come three thousand miles away. Sad now with autumn

And with my hundred years of woe, I climb this height alone.

Ill fortune has laid a bitter frost on my temples,

Heart-ache and weariness are a thick dust in my wine.

Which I suppose is why this appeals to me – there’s a rare clarity here, even if the translation might be inaccurate.

So the Tang poets seemed like the right place to start with for my experiment with machine-generated art (and besides, the excellent GWERN already did the usual English[1]). Right now, I’ve snuck away for a few hours from a my statistical models to peek at the code I set to run this morning.

Among those of us who work with machine learning, the work I’ve put into this whole project is trivial: a tiny dataset, a cup of coffee, a few lines of Python code, and a single cigarette while I waited for OpenAI’s transformer-based generation model [2] to download.

The OpenAI model, like most neural networks, can be thought of as a rough analogue of a human brain – a collection of artificial neurons strung in layers, lighting up as fragments of thoughts (inputs) pass between one layer and the next. We teach it by pointing it at something and telling it to produce something similar. The boffins at OpenAI have decreed that their full model is too complex and human-like to release – God knows what people might do with it in this age of fake news – and so they’ve banged the drum and let out only a tiny, child version of their beast, the GPT2 117M.

No matter. We shall use the child. I’ve set it to train on a collection of Tang poetry, and given my personal biases, both Li Bai and Du Fu feature prominently in here. It has digested and spat out some poetry at me, and I, acting in a role much like a subeditor at a newspaper, am going over copy turned in by the new journalist.

Here are our first results: six poems handpicked out of ten efforts. My edits have been to delete no more than two lines per poem.

ENDLESS YEARNING I

I am endlessly yearning

To be in Baok Sha.

…Insects hum of autumn by the gold brim of the well;

A thin frost glistens like little mirrors on my cold mat;

The high lantern flickers; and. deeper grows my longing.

I lift the shade and, with many a sigh, gaze upon the moon,

Single as a flower, centred from the clouds.

Above, I see the blueness and deepness of sky.

Below, I see the greenness and the restlessness of water….

Heaven is high, earth wide; bitter between them flies my sorrow.

Can I dream through the gateway, over the mountain?

Endless longing

Breaks my heart.

ENDLESS YEARNING II

The sun has set, and a mist is in the flowers;

And the moon grows very white and people sad and sleepless.

Would that it might follow the spring wind to Yanran Mountain.

Since nobody can bear to you the burden of my song,

I think of you far away, beyond the blue sky,

And my eyes that once were sparkling

Are now a well of tears.

… Oh, if ever you should doubt this aching of my heart,

Here in my bright mirror, come back and look at me!

This isn’t the best poetry I’ve seen, but it isn’t the worst. Parents, I understand, try to get children to write poetry all the time – mine certainly did – but it generally takes many years before the little bundle of joy stops shitting their diapers and decides to take on Robert Frost. I’ve spent maybe three hours of my time on this so far, and most of that was spent sorting out code issues.

THE HARD ROAD

I would cross the Yellow River, but ice chokes the ferry;

I would climb the Taihang Mountains, but the sky is blind with snow….

I would sit and poise a fishing-pole, lazy by a brook —

But I suddenly dream of riding a boat, sailing for the sun….

Journeying is hard,

There are many turnings —

Which am I to follow?….

I will mount a long wind some day, and break the heavy waves

And set my cloudy sail straight and bridge the deep, deep sea.

DOWN ZHONGNAN MOUNTAIN

Down the blue mountain in Feng district

You have found your home.

The wind is beating at us, beating at our ears,

And we see only the dark clouds;

We hear only the low wind rustling grasses

Under the quiet river;

And the farmers all are returning what they have,

Washing their fields and burning them.

The GPT2-117M model seems, to mine untrained eyes, to have picked up the ‘form’ of Tang poetry more efficiently. Some rote phrases are inevitable given how small this dataset is, but I’m surprised at how little there are. With a few careful cuts – a line pruned here and there – I can bring out the impression of one overarching emotion. I’m particularly proud of this:

THE LAMENT OF THE ATTACKING EMPEROR

Soldiers are sent north to guard the City of Silk

And east to receive the rain from the Spears of Heaven.

The south runs its wall, the stars are rising,

And our footprints are three hundred miles away.

How can I bear to sweep them away?

A vanished river is forgotten by the people….

Who knows if it is still alive?

… Who knows if it ever was?

Those last two lines, I have to stress, are most definitely not mine.

---

There’s a man I keep coming back to whenever I see something like this, and that’s the chessmaster Gary Kasparov. Kasparov is possibly the greatest human chess player we have seen to date; from 1986 to 2005 he was the world’s best at the game.

In 1997, Kasparov was defeated by a machine – IBM’s Deep Blue. The move changed chess history [3], and I think – looking back – that’s really where the “human vs machine” fear _really_ hit home. Ever since then, chessmasters – the human kind – have accepted getting thrashed by machines.

What did Kasparov do? Kasparov went away and made computer-aided chess work. He took human vs machine and made it human + machine. His thesis is in the title of his TED Talk – “Don’t fear intelligent machines; work with them” [4]. Today, some of the world’s most powerful players are cyborgs – combinations of human players and machine intelligence – and they are damned difficult to beat [5].

I believe in this human + machine philosophy. Over the next year or so, I’m going to be launching more little experiments along this line. Let’s get see where it gets us.

---

A friend of mine, a mathematician, recently posited to me that the role of poetry was capture intricate emotion; I countered by saying the role of poetry was to convey information through the ordering of words as much as the words themselves. But in both our arguments there was the implicit understanding that there _was_ a poet, some creator with a sense of purpose, be it information or emotion. I wonder if we can have the same argument about this, or whether we have to start that argument again with several biases removed.

---

[1] [https://www.gwern.net/RNN-metadata#finetuning-the-gpt-2-small-transformer-for-english-poetry-generation](https://web.archive.org/web/20210510023646/https://www.gwern.net/RNN-metadata#finetuning-the-gpt-2-small-transformer-for-english-poetry-generation)

[2] [https://openai.com/blog/better-language-models/](https://web.archive.org/web/20210510023646/https://openai.com/blog/better-language-models/)

[3] [https://www.chess.com/article/view/deep-blue-kasparov-chess](https://web.archive.org/web/20210510023646/https://www.chess.com/article/view/deep-blue-kasparov-chess)

[4] [https://www.ted.com/talks/garry_kasparov_don_t_fear_intelligent_machines_work_with_them?language=en](https://web.archive.org/web/20210510023646/https://www.ted.com/talks/garry_kasparov_don_t_fear_intelligent_machines_work_with_them?language=en)

[5] [http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20151201-the-cyborg-chess-players-that-cant-be-beaten](https://web.archive.org/web/20210510023646/http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20151201-the-cyborg-chess-players-that-cant-be-beaten)

*edit note: this article formerly read “GPT 2 110M” instead of “117M”. Fixed.

The ease at which I was able to do this intrigued me, because the intersection of stuff that I was working in, public policy misinformation, hate speech, corpus linguistics - everything I knew - was telling me that there would be a future where these sorts of models could be incredibly easily trained to produce misinformation at scales never seen before - and so it was worth checking these things out.

In fact, this led me to participate in an exhibition by the Alliance Francais - an artistic way of showing our dystopian future, if you will.

But back to the poetry. At the time, Rupi Kaur and other Instagram poets were rising to fame and there was a general trend of people posting really shitty poetry on their Instagrams. Effort varied, but in general these people actually put more effort in the imagery of the words on the page than the actual words on the page.

I realized that my little machine poet was actually decent - better than a lot of tryhard Instagram poets. And so I created for it an Instagram handle. Here’s an early screenshot:

OSUNpoet (@osunpoet) • Instagram photos and videos

I call it OSUN. Why? I have very little idea. Presumably it had something to do with zero sum, but by the time I’d finished creating the handle I couldn’t remember why. It just felt natural. Anyway, OSUN had an Instagram page.

Automating interactions was easy. Do you know how simple behaviour patterns are? Particularly on networks like Instagram? And soon it had people following it, liking its stuff. I actually used insights from this to point out at a talk I gave at NATO Stratcom that touched on the dangers of AI powered bots on social media. Especially ones that could maintain very complex behaviour patterns that would evade traditional bot or not scans.

What was difficult were those images, which took quite a bit of effort on my part using GIMP. I made those by hand, I arranged the poetry by hand. It was really a bit annoying, but I managed to keep it up.

I didn’t know what else to do with this thing until a friend of mine, Dr. Samuel Peralta, came along. Samuel Peralta is a polymath. That is the only way you can really explain this man. A physicist and entrepreneur who has designed nuclear reactors, edits long running science fiction anthologies, and writes poetry: even putting this in a paragraph is doing him a disservice. Here’s a better introduction, taken from this Q&A: Samuel Peralta — PoetsArtists

Dr. Samuel Peralta founded the Lunar Codex, archiving the works of over 30,000 artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers from 156 countries on the Moon, in tandem with NASA’s Artemis program. He is an award-winning physicist, a Wall Street Journal and USA Today bestselling author, a Grandes Figuras awarded composer and lyricist, and a producer of Golden Globe-nominated and Emmy-winning films. He has curated exhibits with PoetsArtists, 33 Contemporary Gallery, the Zhou B Art Center, and the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art. He and his wife are named sponsors of the permanent Yayoi Kusama room at the Art Gallery of Ontario. And he cooks a killer penne alla boscaiola.

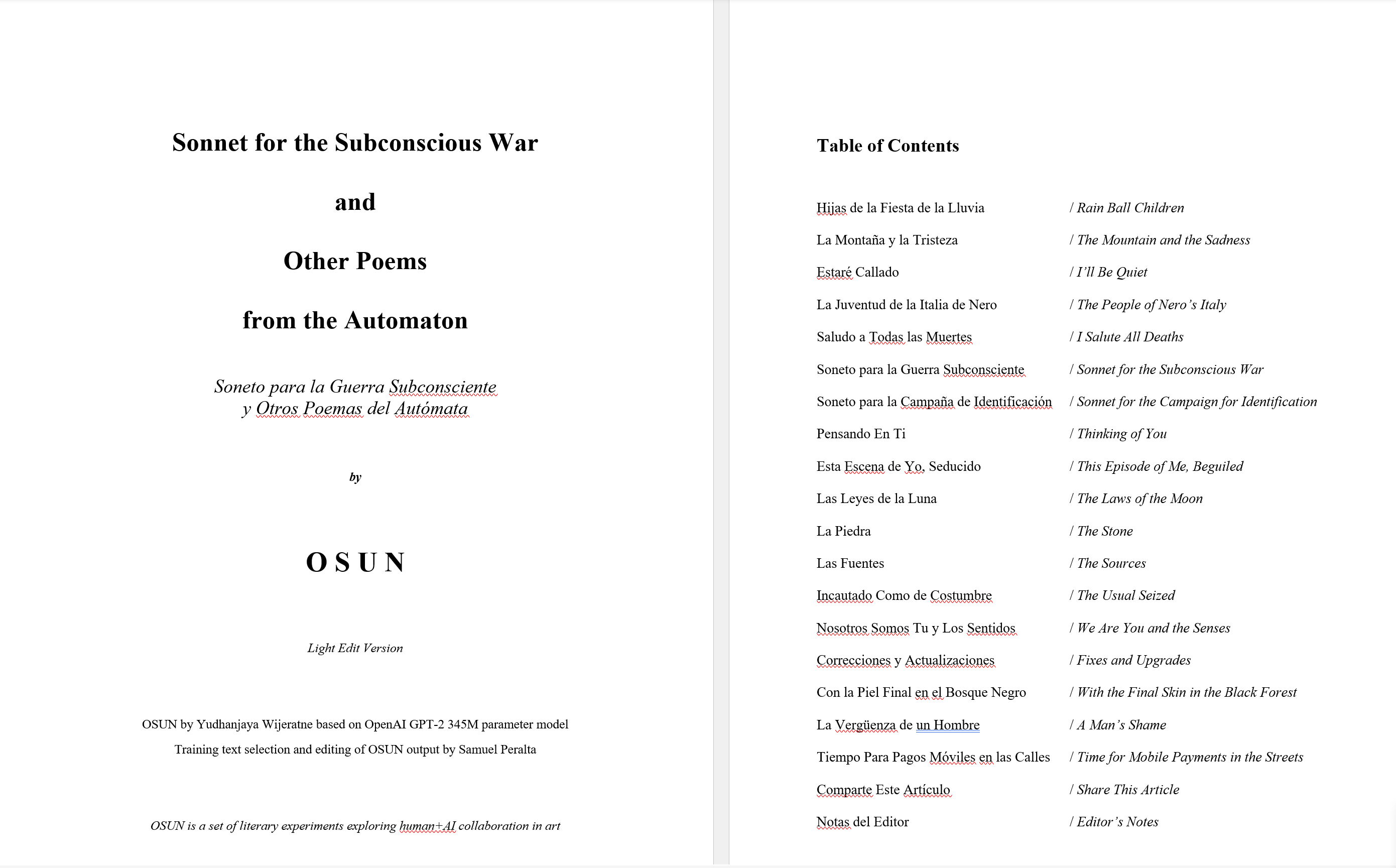

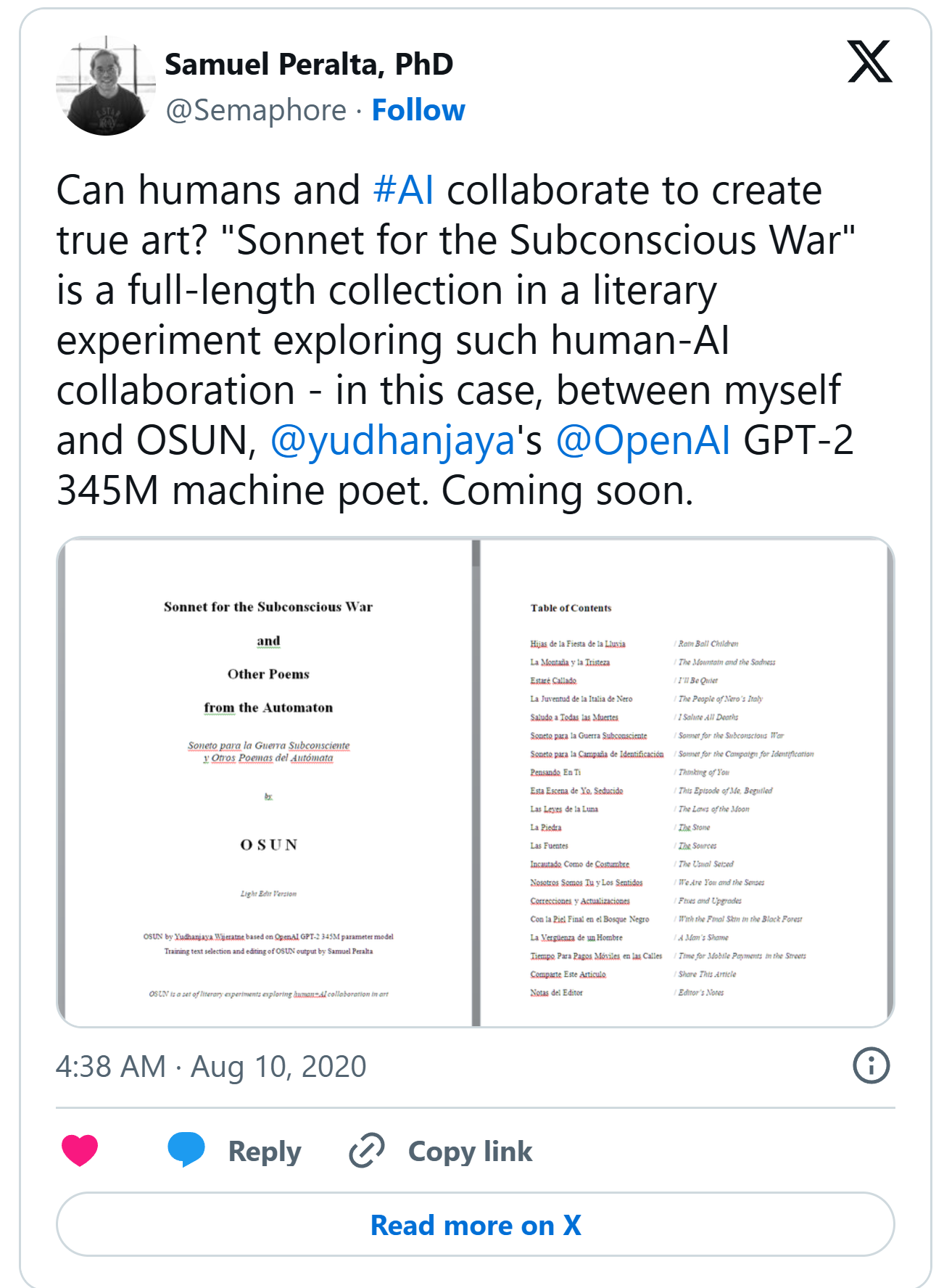

Between the two of us, we produced this.

In the course of doing this, I decided that I was going to use OSUN as the base for my book, The Salvage Crew. I’ve been through over 800 poems, finding interesting artifacts, stitching together lines, turning them all into this vision I had in my mind of the machine poet that is central to the Salvage Crew. Now that book went on to really be a watershed moment for my career . . .

. . . but back to OSUN.

Notice how in the bio above, there was a blurb about the lunar codex? Well, yes. Samuel decided that he was going to embark on this ambitious program of sending stuff to the moon. And among the stuff that went there was an anthology edited by myself; anthologies that I had participated in; and a book called Sonnet for the Subconcious War and Other Poems from the Automaton by OSUN.

In his own words, from the faq:

Q. How did the The Lunar Codex come about?`

A. In late 2019, I was asked to curate an exhibit at the 33 Contemporary Gallery in Chicago, which was to run through 2020. In March 2020 that changed to an online-only event when the world went on lockdown. The theme for the exhibit was Shelter.`

About a year earlier I'd learned about NASA's CLPS program through research for Aircari, a logistics start-up I mentored. In 2020 I re-visited CLPS and found that it had progressed to the point that some CLPS companies were now making space available in their lunar landers for non-NASA payloads. In July 2020, I purchased a DHL MoonBox via Astrobotic, planning to place Moonstone, a piece etched, to last in perpetuity, on a silver metal disc.`

The joy this payload gave me, even before launch, swirled in my mind. Could I share that joy with other artists? The artists of Shelter? I began to search for space on Peregrine to include them, and artists from the circles I was in.`

Several months later, I joined a project assembling a library for the Peregrine mission. As an author and series editor of the Future Chronicles anthologies, I shared my space with the authors, artists, and editors in my series, validating the joy.`

Inspired, I secured more space on Peregrine via Future Grind, then on other missions, including purchasing hundreds of Lunagrams via GLL slated for the Odysseus mission, space via LifeShip on Firefly Aerospace's Blue Ghost lander, RGB NanoFiche archives on the Odysseus, NnoFiche and MoonBox resources on Astrobotic's Griffin lander, and on NASA's Orion spacecraft.`

I sought out collaborations with major art publications and major anthologies, and eventually governmental agencies. I commissioned poetry collections and art competitions, intending to add these to our burgeoning collection.`

With these cultural collaborations, more payload space, and better technology - NanoFiche instead of silver discs, TB of digital memory instead of MB, nickel-shielding, ceramic-matrix, quartz nanochips, and synthetic DNA technology - I brought my manifests to over 5,000, then 10,000 and now over 40,000 creative artists.`

Q. Is there really work from an A.I. onboard?`

A. We have a collaborative poetry collection between myself and OSUN, an A.I. based on an OpenAI GPT-2 model programmed by my friend Yudhanjaya Wijeratne, from Sri Lanka. It was included in our Peregrine mission payload in October 2020, well before the explosion in large language model based tools such as GPT-3/4 beginning in 2023. Despite the new A.I. tools, we value tightly controlling the training database of OSUN. We did not allow OSUN to scrape the Internet. With this caveat - looking at how the A.I. was created and used, we included a handful of A.I.-aided works from the U.S. and one A.I.-aided short story from India. To the best of our knowledge no other substantive A.I. work is included.

This project might be the single most self-underrated thing I’ve ever done. From my perspective, I did something because I was interested in it, and moved on. Not only the stuff ending up on the moon, but I also learned how to use Python fluently; I took an early leap into a nascent subfield at a time when not a lot of people around me knew the subject. And this became the basis of so many things that I did afterwards.

Writing this down showed me how mighty a tree this grew.